Dario Mohr is a multidisciplinary artist based in New York City whose work explores themes of heritage, Black identity, and reclaimed spirituality. Mohr, who was born in the U.S. and is a first-generation Grenadian-American, describes his work as involving the creation of “sacred spaces”—three-dimensional altars and installations that weave together images, lights, plant life, and more in an invitation to explore lost ancestral connections.

For many people of African descent, says Mohr, there is a shared experience of having “been severed from the totality of our history.” Mohr’s recent work—including “Blood Is Thicker Than the Water That Separated U.S.,” which opened at the Lewis Latimer House Museum in Flushing, Queens, last year, and “Temple of Acacia,” an installation at Old Stone House in Brooklyn—grapples with this legacy of colonization and slavery, while extending out into the future, lifting family histories, landscapes, and rituals into sites of worship.

Mohr is also the founder and director of the AnkhLave Arts Alliance, a New York City-based nonprofit that supports Black and Indigenous people and people of color in the contemporary arts. This year, the AnkhLave Garden Project has offered fellowships to six NYC-based artists who identify as BIPOC to create outdoor artworks at Brooklyn Botanic Garden on the theme of “trees as community hosts.”

In celebration of Black History Month, we spoke with Mohr about reclaimed histories and creating inclusive spaces in the arts.

Your work often touches on ancestral rituals and spiritual beliefs. What inspired these themes?

Growing up, I always had an interest in spirituality, despite leaving the Anglican faith as an adolescent. My practice includes installation-based sculptures and altars that in some way harken to spiritual themes. There were several events that set me on a path toward embracing the spiritual and ritual practices of my ancestry. In 2019, I lost a ring that my grandmother had made for me in Grenada. That was the only possession from her that I had, and she passed away in 2013. Losing that ring in some ways felt like I lost a piece of my grandmother’s memory. It was a custom-made gold ring and it had my first initial on it. I’d had it since I was an adolescent.

Although losing it was a blow, the New York lifestyle did not allow me to slow down and feel my feelings. The pandemic kind of knocked me over, and made me reflect on things that I’d been avoiding—the loss of my grandmother, and my regret around not being able to go to her funeral in Grenada nearly a decade ago, and just certain things that made me want to reconnect with my family more. I hadn’t gone back to visit Grenada since before she passed away in 2013, and these feelings that bubbled up so many years later made me realize that it was very important that I honor her. This led me to create a painting series called “Don't Let It Slip Through Your Fingers,” which I exhibited at the end of my residency with Flux Factory. It included several images of hands and other elements alluding to this—what happens to memories when an object that represents those memories is lost.

That was the precursor to some other projects that were more directly related to my ancestry and that of other groups of people who are not always represented here in the States.

Hands are a recurring image in several of your pieces. What does that represent for you?

In high school, I would be drawing in the margins of my math papers—drawing and looking at my hand in different poses. I think it really helped me develop my skill.

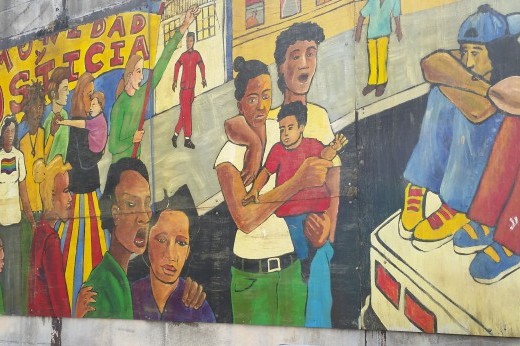

Hands, in their own way, tell us a story of identity. I’ve used hands in self-portraits; I’ve used hands to represent different people of BIPOC communities. For example, I created a mural for ArtBridge that's currently on display on Alexander Avenue in the South Bronx. I incorporated some images of hands that were used for “Don’t Let It Slip Through Your Fingers,” and also took photographs of hands of people living in the Mitchell Housing District, which they volunteered to have taken. I included imagery related to the feeling of cooling down, too, as an acknowledgement of the urban heat island effect that affects redlined communities.

That digital mural is on display on the scaffolding in that neighborhood as a way to build community pride for people who are represented there—and also as a billboard to let neighboring communities that are gentrifying the space know that this has been in recent history a predominantly BIPOC space, and it should remain that way.

How do plants play into your understanding of these ongoing histories of oppression and healing?

My family and I moved a lot. So we lived in San Francisco for a bit, we lived in other parts of New York, like Binghamton, Buffalo, Manhattan, and Queens. In some places that I’ve lived, I remember going to school and during recess, we’d go out into the woods. That was such a freeing experience— as nature inspires a lot of curiosity and interest in the world, and animal life, which I think is really healthy for young children to explore. Unfortunately, many people that I’ve grown up with—of all backgrounds, but especially people of BIPOC heritage, depending on the neighborhood that they live in—haven’t had the experience of wonder, or the therapeutic and mental health benefits that nature and plant life can provide.

In the series “Blood Is Thicker Than the Water That Separated U.S.,” I incorporated birds-of-paradise and other plants that are native to Grenada. Plants can be a beautiful symbol of heritage, and it’s a way to normalize, and venerate, what plants could represent for our health.

.jpg)

You traveled to Ghana, Benin, Togo, and Nigeria, and integrated those experiences into the “Temple of Acacia” series, which is dedicated to spiritual practices in West Africa. What did you take away from those experiences?

One of the major motivating factors for me going to West Africa was understanding how to link my Grenadian ancestry, which really has no recollection of Africa, to that land. I ended up taking an African ancestry DNA test. It acknowledged that we have Akan ancestry on my grandmother’s side, we have Ga ancestry on my grandfather’s side. When I went to Africa, I was very interested in learning more about the Akan people (a tribe historically based in Ghana) and the Ga people.

I met with a tour guide named Confidence, and we drove from Accra to Kumasi, a city in the Ashanti region, where I explored some museums and sacred sites. Among the sites visited was Bonwire, one of the last remaining authentic traditional Kente weaving facilities, where I purchased a giant Kente cloth piece that I used in my “Temple of Acacia” solo show at Old Stone House. We drove through borders from Ghana to Togo, Benin, and then Nigeria. There were many highlights along this journey, including a visit to the Grand Fetish Market, the largest voodoo market in the world, as well as visits to “slave castles” and UNESCO heritage sites.

I understood that the whole region was the stomping grounds of my ancestors. Of course, there were language barriers once we got to Benin and Togo, because they speak French, but I gained so much knowledge seeing the very different cultures, architecture, lifestyles, the slightly different food. All of those things were food for thought that I brought back with me for the “Temple of Acacia” series, to really highlight and honor the African spirituality that, while it translated so much into Grenadian culture, was lost in translation for my recent ancestors from the island.

You also recently went back to Grenada. What was that like?

After I lost the ring my grandmother gave me, and took time to acknowledge her, I really knew that I needed to go back to Grenada. My mother and I went for the first time together in a decade in February of 2022. We were able to refamiliarize ourselves with the island and we visited family members, looked through photo albums, and I gathered objects and material for the “Blood Is Thicker Than the Water That Separated U.S.” series.

What was it like to visit as a child?

I would go for the summers. I remember at around eight years old, I spent my entire summer there. I got so sunburned—I’d only gotten sunburned once in my life, and it was during that summer, due to one afternoon wading in the ocean. I reflect on this experience fondly.

I really missed it—I missed my grandmother, I missed some of the animals that I would see, including geckos that they called “wood slaves.” It was nice going back after all those years and rediscovering things that I had forgotten about, and meeting with family again. We walked through my family’s lands, and I used a video recording of that in Tentacles Across the Sea, which is part of the “Blood Is Thicker Than the Water That Separated U.S.” series. I projected that video onto an old Dutch colonial map from the 1600s.

This was a way to honor the fact that there are parts of the world where Black people own the land—we don’t only have to look at the colonial misfortunes we’ve experienced. There are people who have done and continue to do many great things for our community who we could look to, to remind us that even though, yes, the vestiges of an enslaved history are here, there’s also so much we’ve achieved, and so much more to come.

Speaking of accomplishments, you’ve presented work at the Lewis Latimer House Museum in Queens, and you’ve spoken about Lewis Latimer’s achievements. What resonates for you in his story?

I went to school in Flushing, Queens, and his house wasn’t too far away. We never learned about him in elementary school, which is a shame. I would have loved to visit on a field trip. But I learned about him in my adulthood, and I was impressed, you know? He worked with Thomas Edison, he created the carbon filament for the light bulb, he created a prototype for an air conditioner, and he had a hand in creating the patent for the telephone.

There were a lot of different things he contributed—not just as an inventor and innovator, but also as an artist. When I paid a visit there, I realized, wow, he was also creating pastel pieces and paintings, and I learned that he was a composer after inquiring about the piano there. I just felt like I really connected with him, being someone that has many varied interests myself and is in awe of innovation. It was probably harder to be Black and prolific at that time than now, so I really admire him.

What do you hope that people coming to see your work might take away from it?

Especially if they’re African American or Caribbean American or Caribbean—I think that those different experiences are similar in that we’ve been severed from the totality of our history. I felt like “Blood Is Thicker Than the Water That Separated U.S.” was my way to seek some kind of reclamation of lost ancestral heritage and identity. Hopefully, in some ways, it may inspire others to explore their family history as well.

How did the AnkhLave Arts Alliance get started?

I went to college in Buffalo, and I spent some years during and after that exhibiting around that city, and I realized that I was not only the only Black person but also the youngest person in that scene, making it somewhat difficult to gain traction. I had friends outside of the art community who would come—musician friends and poets and people in other creative niches—but they definitely felt like it was a polarizing space for them.

Eventually, I ended up collaborating with the Black-owned Juice Bar for their grand opening, and I was asked to host a monthly open mic night. That really galvanized me, because the people that were coming to that and performing were predominantly Black. They were excited to come back monthly to build the creative community, and the set list was getting larger each month. When I moved to New York City, I wanted to continue what I was doing in some way. We decided to focus on contemporary art, and we felt like the most equitable space to present art is outdoors. A white-walled space felt like it could be polarizing to some people, and falling within certain traditions that are’t relevant and inclusive of all experiences.

What do you hope to accomplish with the AnkhLave Garden Project?

When I started creating AnkhLave, early on, I remember thinking that we shouldn’t be so focused on asking for inclusion in a space, or a seat at the table—we should make our own table.

The second, third, and fourth Garden Projects, we did at the Queens Botanical Garden. I remember spending a lot of time there in elementary school, since I went to school in Flushing, Queens. I remember talking to my peers, and many of them had never been to a gallery or museum, not only because these institutions were far away, but there was a stigma within our community that they were spaces for white audiences—not them. For this reason, I aimed to provide programming beyond the white-walled gallery and in public spaces.

When I was young, allergies and all, I really enjoyed my time in nature, and during the times we moved away from it, I really missed it. BIPOC communities in urban areas often have fewer opportunities to experience nature. I wanted to encourage more people like me from BIPOC communities to spend time in natural green spaces, and to discover artists from similar backgrounds—encouraging them to take a stake in the contemporary art culture as spectators, and potentially as artists.