I used to hate rainy days. The drama of each passing storm escaped me. I'd sulk inside, waiting for the leaden clouds to lift. Then one day, as a nor'easter lashed our Shelter Island, New York, home, my husband, Don, and I watched the storm water come gushing down our gutters, creating a gully as it carried eroded soil down the driveway. We decided to figure out how much water rolls off our roof each year, and where it all goes.

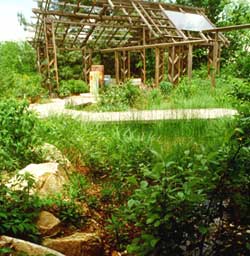

A rain garden in Philadelphia, designed by Edgar David. Rainwater that flows from the house roof to the stone cistern is used to irrigate an intimate collection of woodland plants

Like most people, Don and I didn't think a lot about the earth's hydrological cycle, which supports every terrestrial creature, from human being to towering tree, in the form of rain, fog drip, and snow. Over the ages this precipitation has etched a vast web of watersheds into the planet's surface. However, our huge and costly storm-water infrastructure subverts nature's plumbing system. Rainfall is immediately whooshed from our roofs to gutters and downspouts and channeled by concrete curbs to storm drains and pipes, sometimes in destructive torrents.

In a natural landscape—a forest, say—there's generally very little runoff. The soil and its dense cover of leaf litter and vegetation act as a sponge, absorbing most precipitation. But because we've replaced so much natural groundcover with impervious surfaces, rainfall no longer soaks into the soil as readily as it once did. As a result, huge volumes of runoff flow from countless roofs and compacted lawns down driveways and roads to storm sewers, carrying pesticides, motor oil, and other pollutants to nearby streams and rivers, fouling surface waters and destroying aquatic life through sheer physical force. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that a typical city block generates nine times more runoff than a woodland area of the same size. According to the EPA, storm-water runoff is the leading threat to the nation's estuaries and the third-largest problem facing lakes.

After a few minor calculations, Don and I determined that more than 20 thousand gallons of water pour off our roof each year. (To figure out how much rain runs off your roof, use the formula in the box below.) We wanted to find a natural, low-tech way to dissipate the runoff and encourage it to seep into the soil. We decided to create a rain garden by directing the storm water from our downspouts into a low area we excavated and filled with lovely wetland wildflowers.

Designing With Nature

We located our rain garden behind the house where there was an open area with room for an array of moisture- loving plants native to our local wetland habitats. The southwest-facing area gets a few hours of sunlight before the setting sun dips behind the trees of the surrounding woodland—just enough sunshine to support a decent variety of flowering plants. Because I was determined that our rain garden should attract butterflies and ruby-throated hummingbirds, I included many nectar-rich plants. The garden is at its most spectacular in late summer, when the massive, dusty pink flower heads of joe-pye weed loom high and mingle with the fragrant white flowers of sweet pepperbush and the intense, ruby-colored flower spikes of red lobelia.

My miniature wetland has given me a great deal of pleasure. However, I didn't realize just how spectacular a rain garden can be until recently, when I saw the work of Edgar David, a Pennsylvania-based landscape architect (610-584-5941; www.seddesignstudio.com). In David's gardens, the storm water isn't just whisked safely into a wetland planting; it is celebrated and becomes a focal point of the design. "The flow of water," in his words, "serves as a barometer of the storm," an expression of the natural forces acting on the environment.

The rain garden designed by Edgar Davis at Temple University's Ambler Campus.

In one of David's gardens, on a typical narrow urban lot in Philadelphia's Chestnut Hill, rainwater collected from the house roof cascades into a handsome stone cistern. The water in the cistern can be used to irrigate the intimate native woodland garden that he re-created on the site. Excess water overflows into a recharge basin comprised of stones and gravel beneath the garden path, replenishing diminishing groundwater instead of ending up in nearby streams and causing erosion and other ecological damage. At another rain garden he designed for a suburban setting at Temple University's Ambler Campus, outside Philadelphia, runoff from the roof of an adjacent cottage flows overhead in an "aerial aqueduct," dropping dramatically in two steps on its way to a solar-powered fountain. Storm water running off a nearby terrace is carried by a handsome, plant-lined rocky swale into a native wetland garden. Here some 200 plant species, from bonesets to tussock sedges, filter pollutants from the water as it seeps into the soil.

How to Construct a Rain Garden

But you don't have to be a professional landscape designer to create a beautiful rain garden. A rain garden is really just a strategically located low area where storm water can be captured to soak naturally into the soil.

Begin by observing your landscape when it rains to determine how storm water runs off your property. Typically, the largest sources of runoff are the roof, paved surfaces, and slopes. You can locate your rain garden at the bottom of slopes or next to hard surfaces such as your driveway and sidewalks—along the front walkway or between the sidewalk and the street, for example, to keep runoff from flowing into the road and down the nearest storm sewer. You can also direct runoff from your roof to the side or back yard. Not only will a rain garden along the side of the house catch runoff from your roof, it will also create a handsome living fence between you and your neighbors. Wherever they are located, rain gardens can replace high-maintenance lawn that provides little in the way of visual interest or wildlife habitat. Just keep the plantings at least ten feet from your house—or your neighbor's—to prevent moisture problems in the basement.

There's no regulation size for a rain garden. Home rain gardens installed by the city of Maplewood, Minnesota, which since 1999 has made these gardens a regular part of its ongoing street-reconstruction efforts, were in three standard sizes: 12 feet by 24 feet, 10 feet by 20 feet, and 8 feet by 16 feet. However, a planting of any dimension will help reduce the runoff problem. If you are technically minded, you can calculate the area of your rooftop and average storm-water volumes in your vicinity (or the volume of your sump pump, if you have one) to determine exactly how large your garden must be to capture rainfall from all but the biggest storms (consult one of the technical design manuals listed in Resources).

Unless you've got a naturally low area in your landscape, you'll need to create a depression by excavating soil. Typically, the deepest portion of the rain garden will be about six inches below the level of the surrounding land.

Some of the topsoil removed from the site will be used to create a porous planting mixture. If your rain garden is located on a slope, you can pack some of the excavated soil along the downhill side to increase the depth of the planting area with less digging. Or you can use the leftover topsoil elsewhere in your yard. It's a good idea to loosen the remaining subsoil in the depression with a shovel or garden fork. Next, return some of the topsoil, amended with compost, and sand if necessary. A blend of 20 percent organic matter such as compost, 50 percent sandy soil, and 30 percent topsoil will promote good drainage and help break down pollutants. Clay content, which inhibits drainage, should not exceed 10 percent of the soil mixture. The proper soil mixture will ensure that there is rarely standing water in your rain garden for more than a few hours, or a few days at most—too short a time to breed mosquitoes, which require about a week of standing water to reproduce.

To direct the storm water from the downspout or sump-pump outlet, attach a length of plastic pipe and bury it in a shallow trench that slopes down to the rain garden. Alternatively, you can simply lay the pipe on the ground or create a grassy swale leading from the downspout to your rain-garden depression.

Choosing Plants

Planting a rain garden is the fun part. A variety of native plants including wildflowers, ferns, grasses, shrubs, and trees thrive in moist soil. Your rain garden can be divided into three wetness zones: In the lowest zone, plant species that can tolerate short periods of standing water as well as fluctuating water levels, because a rain garden will dry out during droughts or at times of the year when precipitation is sparse. Species that can tolerate extremes of wet soils and dry periods are also appropriate for the middle zone, which is slightly drier. You can put plants that prefer drier conditions at the highest zone or outer edge of your rain garden. Plant as many species as you can to enhance your rain garden's value as wildlife habitat.

If your rain garden is shaded by existing trees, plant smaller understory trees and shrubs such as river birch and sweet pepperbush, as well as ferns, sedges, and wildflowers. Re-creating the vertical layers found in a natural forest will provide a number of different habitat niches for a variety of birds and other creatures. If you are planting in a sunny area, a wet meadow full of colorful prairie wildflowers and grasses is an appropriate choice. Gardeners in arid areas should plant the species that grow naturally along streamsides and desert washes, such as acacia, hackberry, and desert willow.

When you're finished planting, add a three-inch layer of hardwood mulch to suppress weeds. The mulch will also remove heavy metals from the precipitation before it percolates down into the groundwater.

Although rain gardens require some initial effort, they are a cinch to maintain. Until your plants become established, you may have to weed out undesirable volunteers. Leave the dormant plants alone over the winter to provide seeds and shelter for overwintering birds and butterflies. In spring, you can cut back or mow the stalks of herbaceous plants if you prefer the neat-and-trim look. Reapply mulch when necessary.

Now that I have a rain garden full of glorious, colorful blooms, I actually look forward to the occasional shower or dramatic downpour. I know that by keeping stormwater from running off my property, my rain garden is helping to promote the health of our local watershed. My rain garden has other satisfactions as well. It creates valuable wildlife habitat, satisfying the needs of brilliant butterflies, peepers, birds, and other wildlife. At the same time, our little wetland planting helps replenish the underground reservoir that provides the fresh, pure drinking water that supports me and my family.